Stop Overthinking Decisions

Not every decision needs a committee, binders of research, and months of hand-wringing

I had a friend once who evaluated every. single. purchase by one criteria: is this my most favorite thing ever? If yes, buy it. If no, don’t.

That’s a pretty high bar for every purchase. Maybe too high?

Not everything in life has to be your absolute favorite. Sometimes “good enough” gets the job done, too.

Like when you just need a t-shirt. Or underwear.

Not Every Decision Is Critical

That same urge to make every choice the perfect one doesn’t stop with shopping. It sneaks into how we make decisions at work, too.

We stress over decisions. We worry that we’re missing information or that we don’t have all the data. We ask for additional analysis and assessment of “dogs not barking” (is this an Amazon thing or do other folks use this term, too?).

Or my own personal fav from my higher ed days: form a committee, spend two years analyzing, and chase a consensus that’s never going to happen. Like, ever. 🙄

Why do we treat every decision with the weight and importance of the most important thing we’ll ever decide?

I’ve written before about decision-making, and it’s worth a read if you want more ideas for growing your high-velocity decision-making skills.

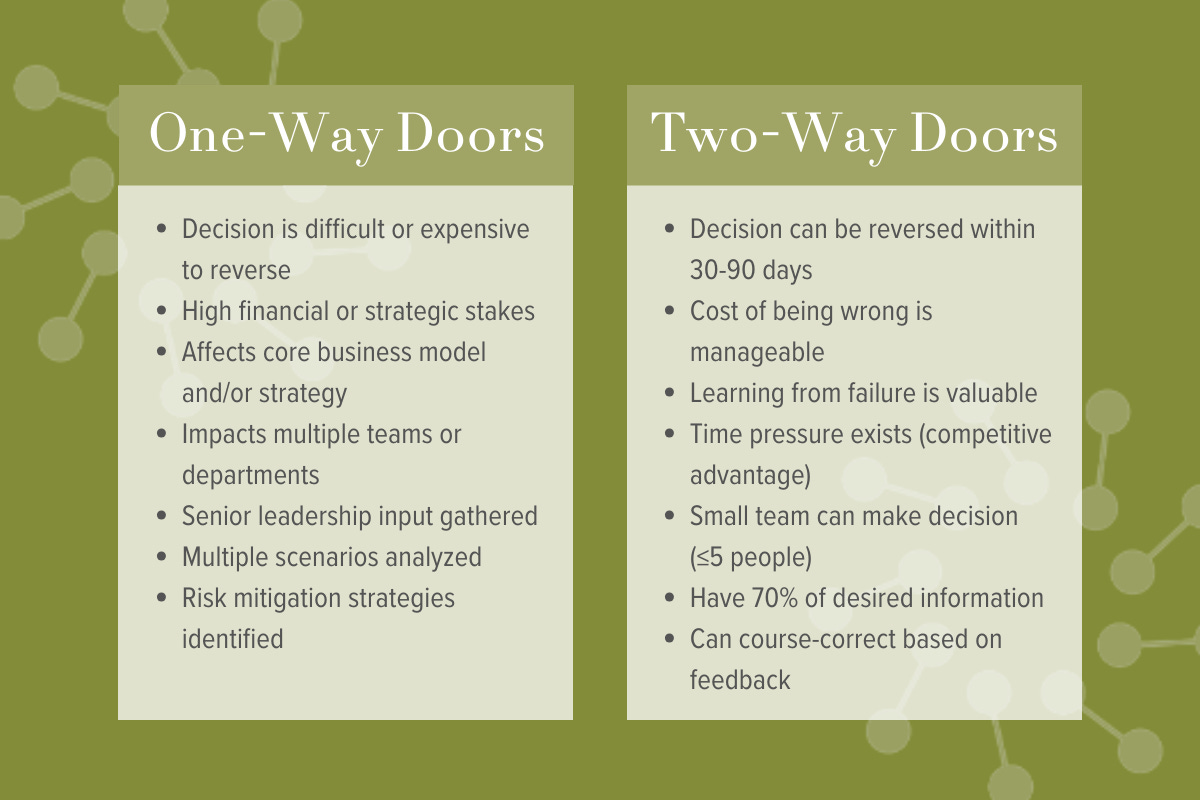

In that article I reference one- and two-way door decisions, which is one of my favorite tools for decision-making. I love this framework because it applies equally well to any decision you need to make—in work or in life.

The Premise Is Simple

Every decision boils down to one question: is this a one-way or two-way door? That is, if I make the decision and later realize that it’s not right, can I walk it back relatively easily?

Decisions that are large, costly, and complex are generally (but not always) one-way doors—like moving across the country in one’s personal life, or closing down an entire product line in a business or program within a university.

Amazon talks about launching AWS as a one-way door decision. It’s extremely difficult to build up the infrastructure and earn the trust of your customers, only to walk away a year or two later and say, “Never mind—we’re out.”

But most decisions don’t carry this level of gravity. There are always ways to mitigate risk, start small, try before fully committing, and walk things back.

And some decisions really don’t matter at all, in the grand scheme of things:

Blue or green for the marketing promo? Don’t care, you decide.

Location of our next offsite? As long as it’s central for all attendees and cost effective, run with it.

Evolving our sales pitch? Try a few things (hopefully in low-stakes calls) and see what sticks.

These should be easy to make—or even better, to delegate.

As for the rest of your decisions, the line between two-way and one-way may be a lot higher than you think.

Most Decisions Are Two-Way Doors

The vast majority of decisions we stress over and make on a regular basis are actually reversible. Even significant changes like starting a new initiative, evolving a program, or reorganizing a team can be two-way door decisions.

Why? Because no one gets everything right the first time.

So getting started on something—that reorg, program evolution, or new initiative—is way more valuable than trying to get it right. Here’s how:

New initiatives

When launching something brand new, framing is key. Engage customers, partners, or students in the process and set clear expectations: we're piloting something new and need your help to decide if it should continue—and if it should, how to iterate and improve it.

This approach actively involves your stakeholders as co-creators rather than consumers of a finished product, helping to de-risk and make the decision reversible.

Program changes

My former team at Amazon made a significant program change: we removed perpetual coverage from partners and moved to a time-based model, where partners would have coverage for 12-18 months and then graduate from the program.

With this major partner impact, you’d think it was a one-way door decision—right?

Nope. If it didn’t work, we could always revert back. Walking it back wouldn’t have scaled the way we wanted, but it wouldn’t have left us worse off either.

Reorganizations

Reorganizations are disruptive and deserve thoughtful planning. But they’re still not one-way door decisions—organizations need to continually evolve.

When I led major reorgs, I told my team we’d probably get about 80% right. The rest we’d fix together, with their input and what we learned along the way.

A colleague of mine, a CIO, went even further—they tweaked their org chart once a year, like clockwork. That annual “tune-up” made change feel normal, instead of a massive upheaval.

While I wouldn’t recommend constant shake-ups, pairing big shifts with steady, incremental adjustments helps move reorgs firmly into the two-way door category.

Making Faster Decisions

If you’re approaching most decisions with the same level of rigor and importance, you’re costing yourself valuable mental capacity, time, and learnings.

Here are four mental model shifts to encourage two-way door decision-making:

Challenge your thinking: If you think more than 10-15% of your decisions are one-way doors, you’re likely setting your bar too low. It’s time to figure out what’s holding you back from two-way door decision-making, and rethink your approach.

Get comfortable with being wrong: Perfect information is rarely available, so optimize for learning quickly rather than being right initially.

Move quickly: Distinguish between decisions that get better with time and/or data, versus those that get worse with delay.

Learn fast: Set up feedback loops and metrics to detect when course correction is needed. Having these in place will bolster your decision-making confidence, knowing that you’ll have the right level of visibility to make adjustments—or even reverse your decision—if necessary.

The next time you’re stuck in analysis-paralysis, remember: most decisions aren’t life or death. They don’t need to be your most favorite thing ever.

Good enough is … good enough. Make the decision and adjust as you go.